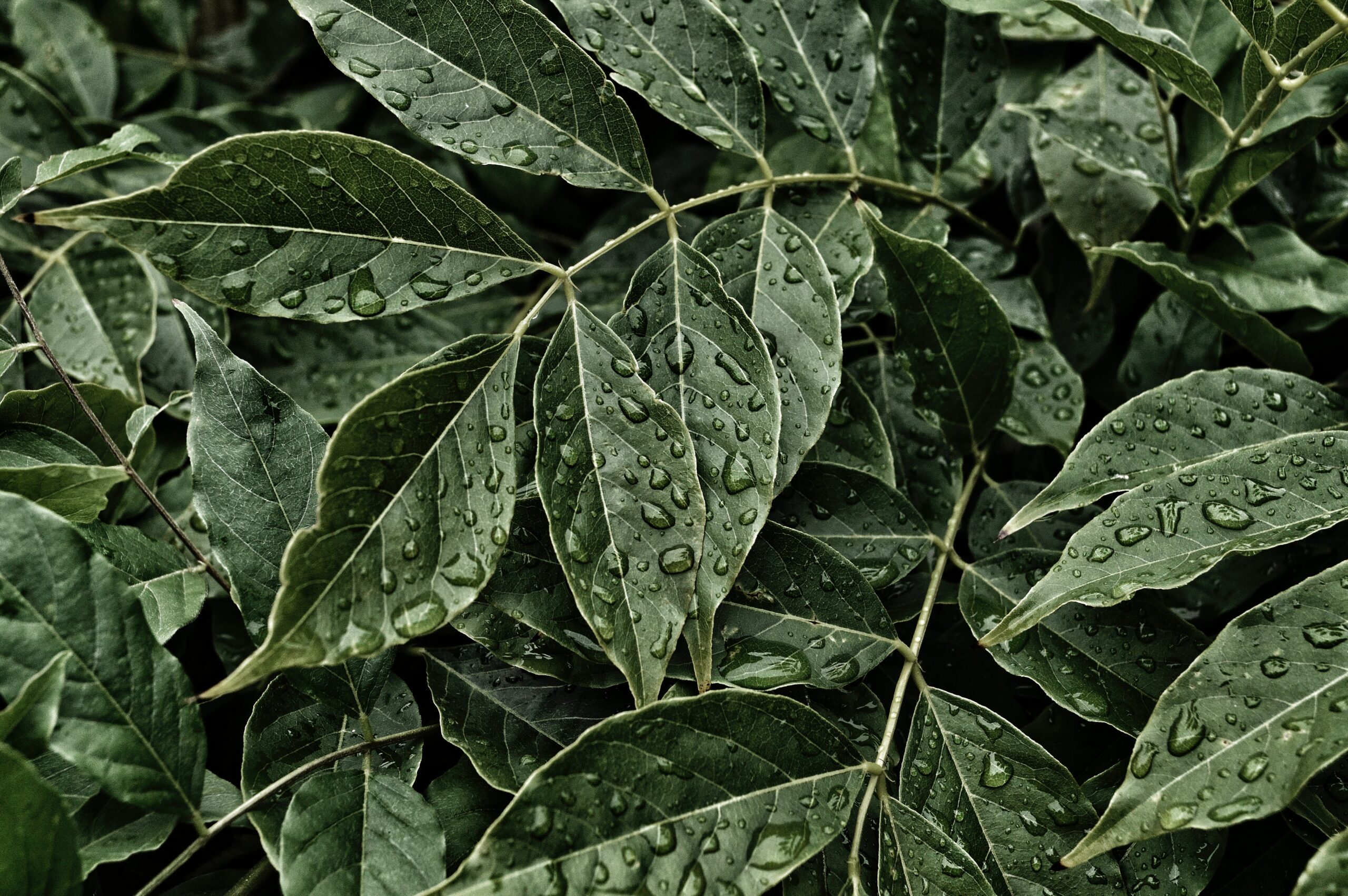

The most pressing threat facing bee populations world-wide is habitat loss and fragmentation, mediated by agricultural intensification over the last century (Baude et al., 2016; Newbold et al., 2015; Potts et al., 2016). In combination with challenges posed by widespread pesticide use (Wood & Goulson, 2017) and emerging parasites and disease (Fürst et al., 2014), this extensive conversion of flower-rich habitat to land that is often nutritionally barren from the bee’s perspective has been strongly implicated as a driver of pollinator declines (Carvell et al., 2006; Potts et al., 2016; Senapathi et al., 2015). Within this context, growing evidence to suggest that flora-rich patches within cities and towns may support diverse bee populations (Baldock et al., 2019; Hall et al., 2016; Theodorou et al., 2020), and that wild social bee colonies in urban areas may outperform their agricultural counterparts (Goulson et al., 2002; Samuelson et al., 2018; but see Milano et al., 2019) has raised the possibility that cities might offer important refuges in an impoverished agricultural landscape. Although usually surrounded by large expanses of impermeable man-made surface, urban parks, gardens and allotments can offer high floral abundance and diversity across the season (Baldock et al., 2019; Plascencia & Philpott, 2017), alongside rich nectar resources (Tew et al., 2020). However, directly comparing forage availability for bees in urban and agricultural environments through ecological surveying presents a major challenge of both access and scale that can be hard to overcome.